The humanitarian and economic ramifications of a modern city not having enough water are almost unimaginable. However, a recent study by the State of Arizona suggests that is precisely the Phoenix area’s peril. New research and analytics by 2NDNATURE suggest strategic stormwater management practices and new investments in new green infrastructure could avert that crisis by turning stormwater runoff into a resource to recharge the groundwater. There are lessons for any city seeking to become more climate resilient.

Watching a train wreck in slow motion

Arizona has been conscious of its water resource limitations for a long time. A desert state largely reliant on water from the Colorado River and groundwater reservoirs, the state’s landmark Groundwater Management of 1980 sought to secure local water resources by ensuring responsible development. Before construction permits are approved, developers must demonstrate that underground aquifers have enough water to meet the new community’s demand for 100 years.

Unfortunately, those policy actions haven’t averted the looming crisis. The projected water deficit for the area is 4.86 million acre-feet. That’s what the findings of a new study released last week by the Arizona Department of Water Resources suggest. Those findings have prompted regulators to announce new construction and redevelopment limitations across the metropolitan area.

Phoenix must find and harness new water sources to expand and flourish. Developers seeking new building permits must find alternative assured water supplies to proceed. It’s time to consider and use alternative design and construction techniques.

Way too much concrete

The modern urban area is full of concrete and other impervious surfaces. That fact causes several significant ramifications. First, buildings, roadways, and parking lots prevent rainwater from penetrating the surface where it falls. Instead, rain hits those impervious surfaces and becomes runoff. That runoff is moved away from the urban area by a series of designed assets, such as drainage canals and pipes. Second, this runoff picks up all the toxins and pollution on the concrete, poisoning our surface waters. Third, impervious surfaces retain and re-emit heat, resulting in higher temperatures in those urban areas. That combination threatens the health and well-being of citizens and organizations conducting business in those areas.

Water is available.

Even in arid places like the desert Southwest, it rains. According to the National Weather Service, the region typically receives more than a foot of rain yearly. National climate change models predict the volume of rainwater falling in the Phoenix region will remain relatively constant over the next several decades. The good news is that the water falling from the clouds is clean.

Turn runoff into a resource.

Research by 2NDNATURE forecasts that rain could result in more than 17.1 million acre-feet of stormwater runoff in the Phoenix area over the next century. That is more than 3x the amount of the projected water shortfall. Rainwater and runoff could be the solution to recharging the groundwater and making up for that projected shortfall.

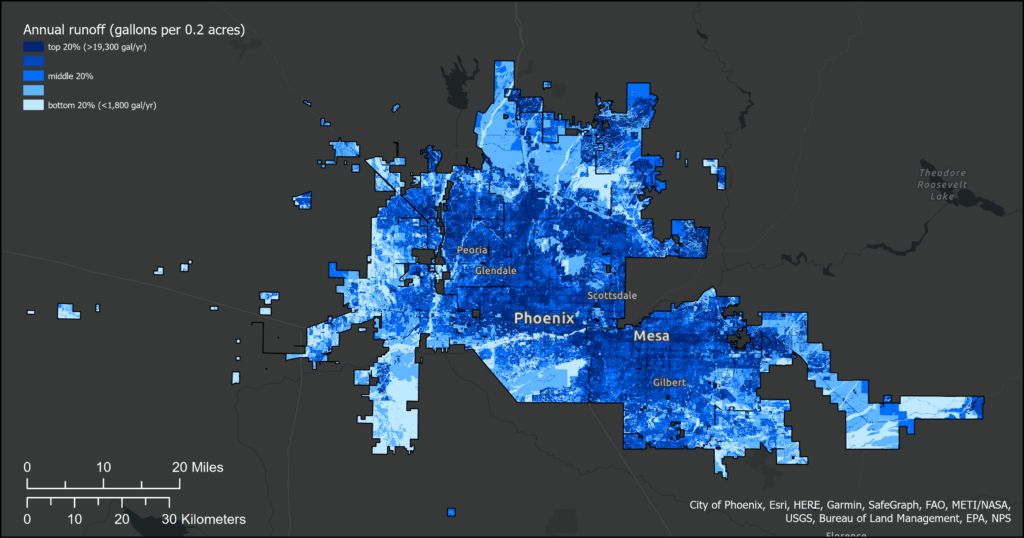

The map below shows the average annual runoff volume using local precipitation/rainfall records. The darkest blue areas get the highest volume of runoff. Look closely and see thousands of tiny squares (pixels). Each pixel is about two-tenths of an acre.

Caption: Fine-scale annual stormwater runoff estimates for the Phoenix AMA (Arizona Department of Water Resources). Estimates were developed using peer-reviewed methods developed by 2NDNATURE. The results above suggest over 17.1 million acre-feet of stormwater runoff over 100 years for the Phoenix region (1.168 million acres).

The model and predictions are based on years of scientific research and field-verified observations. To create those predictions, the 2NDNATURE model uses the best available nationwide data, including precipitation records, land cover, and soils. That data is analyzed and processed according to our peer review methodology using spatial statistics and cloud computing. The results can inform the new policy, legislation, and action to address the water shortfall.

Go from gray to green.

Green infrastructure is the most promising approach for capturing and sinking that water into the groundwater. Green infrastructure refers to a network of natural features and systems intentionally designed and managed to provide multiple benefits to communities and the environment. It incorporates elements like parks, trees, gardens, green roofs, permeable pavement, and wetlands into urban areas. These features help mimic natural processes and provide valuable ecosystem services.

Many practical and cost-effective ways exist to replace concrete and other hard surfaces with green infrastructure. Adding a series of islands filled with shrubs and trees collect runoff in parking lots. Replacing concrete walkways and patios with pavers offers another means for runoff to seep into the ground. Homeowners can install rainwater collection systems like rain barrels or cisterns to capture and store rainwater for various non-potable uses such as irrigation.

By incorporating green infrastructure into our cities and towns, we can create more sustainable and resilient environments, enhance the quality of life for residents, and mitigate the negative impacts of urbanization on both people and nature.

A cautionary tale for other cities

Other cities across the U.S. are facing similar challenges to Phoenix. Green stormwater infrastructure, intentional aquifer recharge, and rainwater harvesting are exceptions in urban planning rather than the norm. It is time to challenge the prevailing practice of covering our cities with vast contiguous areas of pavement. Because of climate change, we urgently need to redefine urban planning and incorporate various methods to capture, store, and manage rain in our cities. Many benefits await us, from reduced flood hazards, improved water quality, decreased extreme heat through increased greening, and ultimately, more diversified local water supplies. Each of these advantages increases resilience against climate change, improves the quality of life, and protects human safety.